With some abandoned places in truly far-flung locations, the mystery is less about why they were abandoned – it is how there were people there in the first place. Take these seven wondrous examples of human stubbornness in the face of extreme environmental conditions, from one temperature extreme to another – and marvel at our ability to leave our mark in the remotest corners of the world, for good or ill.

1. St. Kilda, Scotland

Forty miles into the Atlantic Ocean, the archipelago of St. Kilda is the western tip of the the Scottish Outer Hebrides – and the most windswept, storm-tossed part of Britain with waves up to 5 meters high and recorded windspeeds as high as 130 mph.

Its terrain is monstrously rugged (containing the sheerest drop to sea level in the whole of the UK). The climate is unsympathetic. In short, anyone would be mad to want to live there.

Tell that to its previous inhabitants. Not only are there traces of various prehistoric communities, they also appear to have endured, culminating in continuous human settlement for 2,000 years – ending in 1930 when a combination of factors including accidental pollution of the land, crop failure and an unsustainably low population drove the remaining St. Kildans off the inhabited main island (Hirta) and back to mainland Scotland. The archipelago has been uninhabited ever since.

While there is no permanent population, St. Kilda still enjoys a wealth of scientific and cultural attention. In 1986 the islands became Scotland's first UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is now administered by the National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Ministry of Defense. In addition to the rangers, archaeologists and conservationist visiting and working on the islands, a number of cruise ships and charter boats bring tourists (and their charitable donations) in ever-increasing quantities. Some of the more substantial ruins are being rebuilt to provide tourist attractions – not to mention shelters, when the weather sweeps in.

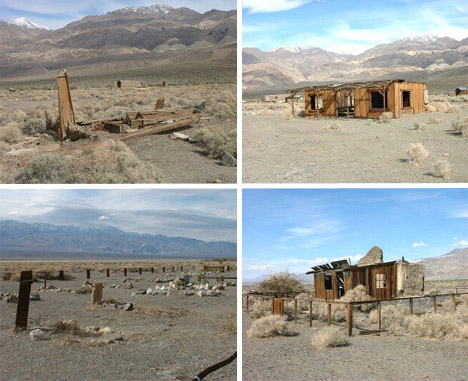

2. Ballarat, California

Three and a half miles off California 178 and a short, dusty drive from Death Valley, Ballarat is a town on the verge of abandonment – and of disappearing altogether.

Named after the Australian town where the largest gold nugget in history was discovered (a whopping 143 pounds), Ballarat attracted enough gold miners to swell its population to 500 souls in the first years of the 20th Century. It was a relaxation station and a watering-hole (all supplies shipped in from afar) for all those seeking their fortunes in the area, particularly at the Ratcliff Mine just to the east of town. When the mine closed, the town began to die – and today, the sun-baked ruins of the town contain just two permanent residents.

3. Dallol, Ethiopia

Fancy living and working somewhere with an average yearly temperature of 34°C (94°F), where summer days never drop below a toasty 40°C? Then you may understand why Dallol in a remote corner of northern Ethiopia's Afar Depression is an uninhabited, uninhabitableghost town.

Even getting there is a tall order – it is extraordinarily remote with no connecting roads. It owes its existence to the local production of potash, enabled in 1918 by the construction of a railway terminal 28km away to shuttle raw materials to Mersa Fatuma. After its short-lived heyday, the settlement fell into decline when demand for potassium salts was met by overseas markets – and when the British dismantled the railway after the Second World War, Dallol's fate was sealed.

Today, the settlement is little more than a series of shattered, crumbling walls of salt-block bricking, littered with rusting vehicles and pieces of mining machinery – and apart from the occasional intrepid visitor, it is out of human influence, out of sight and out of mind.

4. Múli, Faroe

Don't let the intact townhouses fool you – because Múli (population 4) is heading for the history books.

Lying on the bleak northern tip of the Faroese island of Borðoy, Múli has stubbornly clung to existence since the 13th Century, despite lacking a good road and basic utilities (it only acquired an electricity supply in 1970). The road came, but the people left – and while the summer months see a few previous inhabitants returning for a nostalgic vacation, the town is now considered derelict.

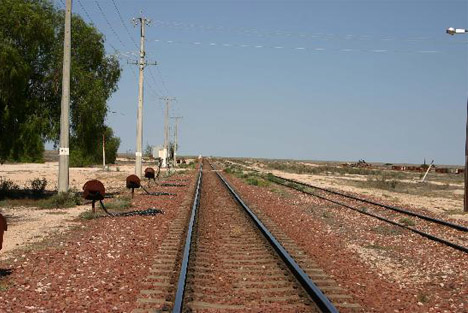

5. Cook, South Australia

If you are lucky to find yourself travelling the 4,352 km of the Indian Pacific railroad in South Australia, be sure to look out for the town of Cook.

Midway along the longest stretch of straight railway in the world (478 km) and the Indian Pacific's only scheduled stop across the Nullarbor Plain section of its route, Cook is tiny and remote, offering little more than occasional overnight accommodation and shopping supplies for train passengers. All supplies, including fresh water, arrive by train – but that isn't a problem as there are only 4 residents, officially making Cook a ghost town.

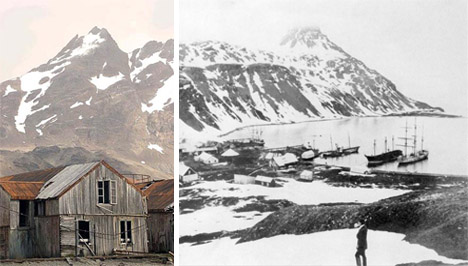

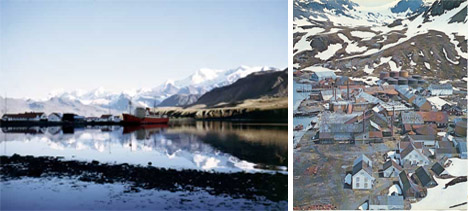

6. South Georgia, South Atlantic

If you thought there was nowhere habitable in the Southern Atlantic beyond the Falkland Islands…well, you are almost right. The British-owned isle of South Georgia may cover a thousand square miles, but every one of them is cold, windy and prone to sleet and snow whatever the time of year. Not somewhere to linger.

During the 19th Century, South Georgia was the home to a number of sealing and whaling communities containing factory ships, land stations and repair yards. In 1916, it was to South Georgia that Shackleton sailed in an open lifeboat from Elephant Island, 800 miles to the south – a staggering feat of not just endurance but also navigation, as Shackleton's crew was only able to take four nautical sightings during the entire 17-day voyage.

The longest-running station operated out of South Georgia's best harbor at Grytviken – established in 1904, it even housed a permanent population until its closure in December 1966. Shackleton used the town to launch his rescue of the members of his crew he'd left behind on Elephant Island – and it was here that he was buried in 1922. His grave still attracts tourists from the cruise ships heading towards Antarctica, and the town's church is still used to conduct remembrance services.

Grytviken is South Georgia in miniature: once thriving with marine industry, now rusting and derelict but enjoying significant through-traffic of tourists, scientists, fishing boats and a British military presence. The latter was ousted on April 3rd 1982 when Argentinian forces attacked and occupied Grytviken. On April 25th, the British returned, bombarded the neighboring hillside with naval artillery to signal their intent, and unleashed a small group of Special Forces and Royal Marines on the town. After 15 minutes, the Argentinians surrendered.

The enduring Argentinian claim on South Georgia led to a heightened military presence in the years after the Falklands War, finally scaling back and handing over their base at King Edward Point over to the British Antarctic Survey, who now staff the base for much of the year – the closest that South Georgia now has to a resident population.

7. Northern Siberia

There are few words that evoke such strong memories – and stronger opinions – as Gulag. The name of a branch of the Soviet State Security, it has instead become better associated with its detention and forced labor camps positioned along the fringes of the Soviet Union, some of them in arctic or subarctic environments.

Of the many hundreds of camps operating during Stalinist Russia, many still remain as ruined memorials to the 18 million people who passed through them – and the estimated million who died there, victims of cold, hunger and inhumanly hard labor.

Most of the camps were positioned in the remotest parts of northeastern Siberia and southeastern Khazakstan, in places of sparse population and few connections. The more remote the location, the less that security was a problem, as the severity of the environment worked as a better deterrent than any fence or guard-tower.

This final instance of remote abandonment is unique from the preceding examples – because it is abandonment without regret. It is unlikely that anyone will look nostalgically back to the days when Soviet gulag camps were operating. The inhabitants certainly didn't choose to be there, and gained little or nothing from the experience. For those reasons, these were places where people lived and died – but probably never regarded as home.

No comments:

Post a Comment